EMR November 2021

Main Lines of Change

Dear Reader

Studying the literature on economic change, while focusing on the post-World War I period, is very instructive, especially as a guide to the current turbulent environment. The available forecasts reveal major economic and social imbalances. We consider them quite significant, especially in the context of current uncertain developments.

Deterministic Facts

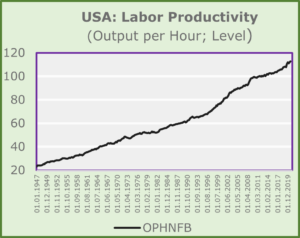

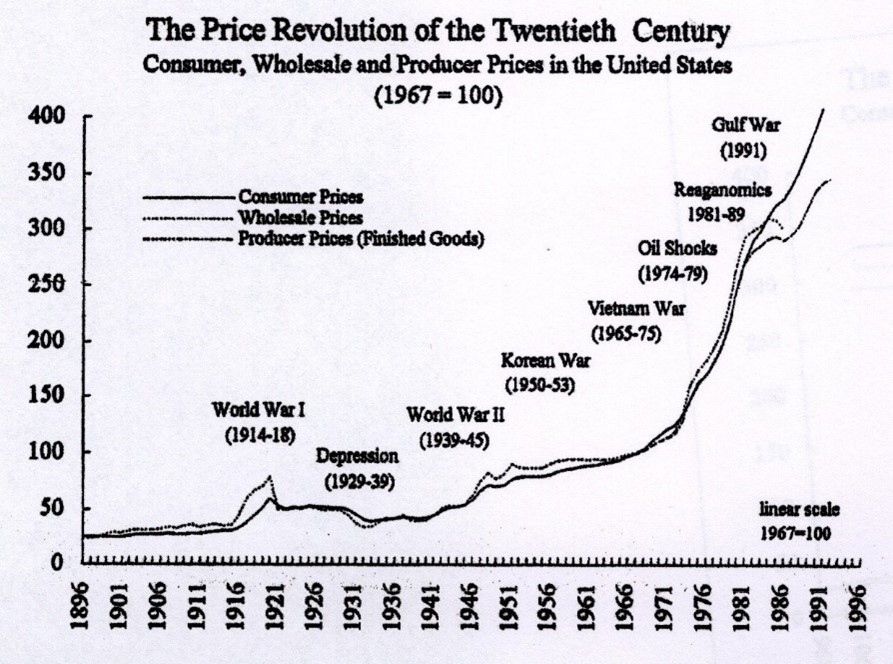

The above chart portrays two very disparate developments. On the one hand we find a rather volatile but smooth increase from 1896 to the late 1960, and on the other hand a dramatic, almost linear increase into 1996. In this EMR we will concentrate our attention to the second phase, i.e., the period since 1967.

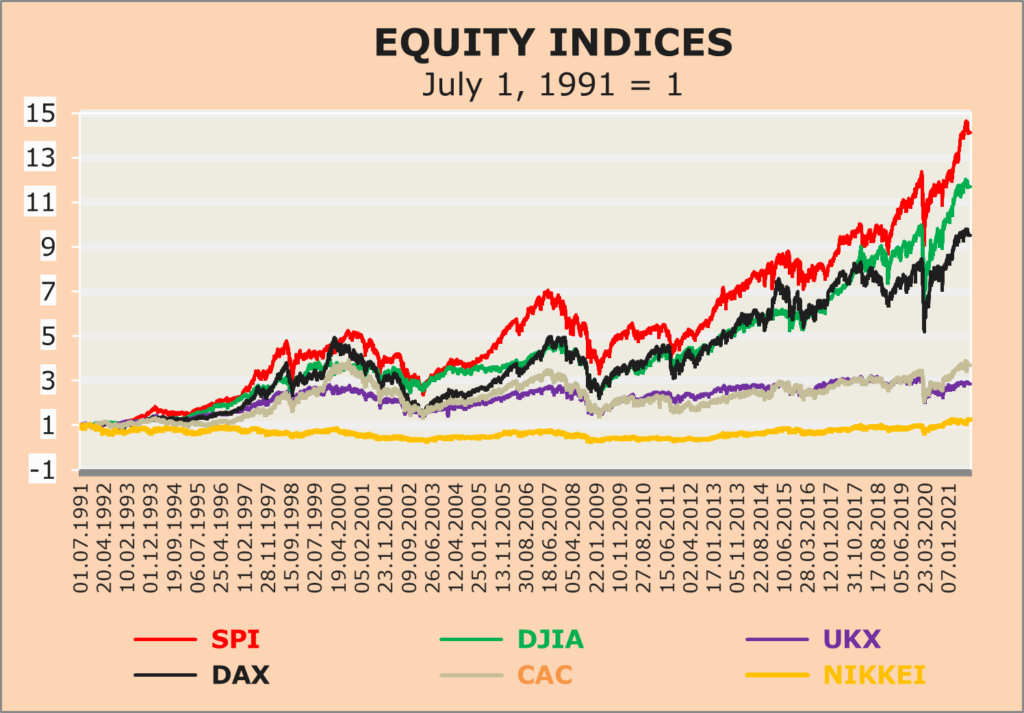

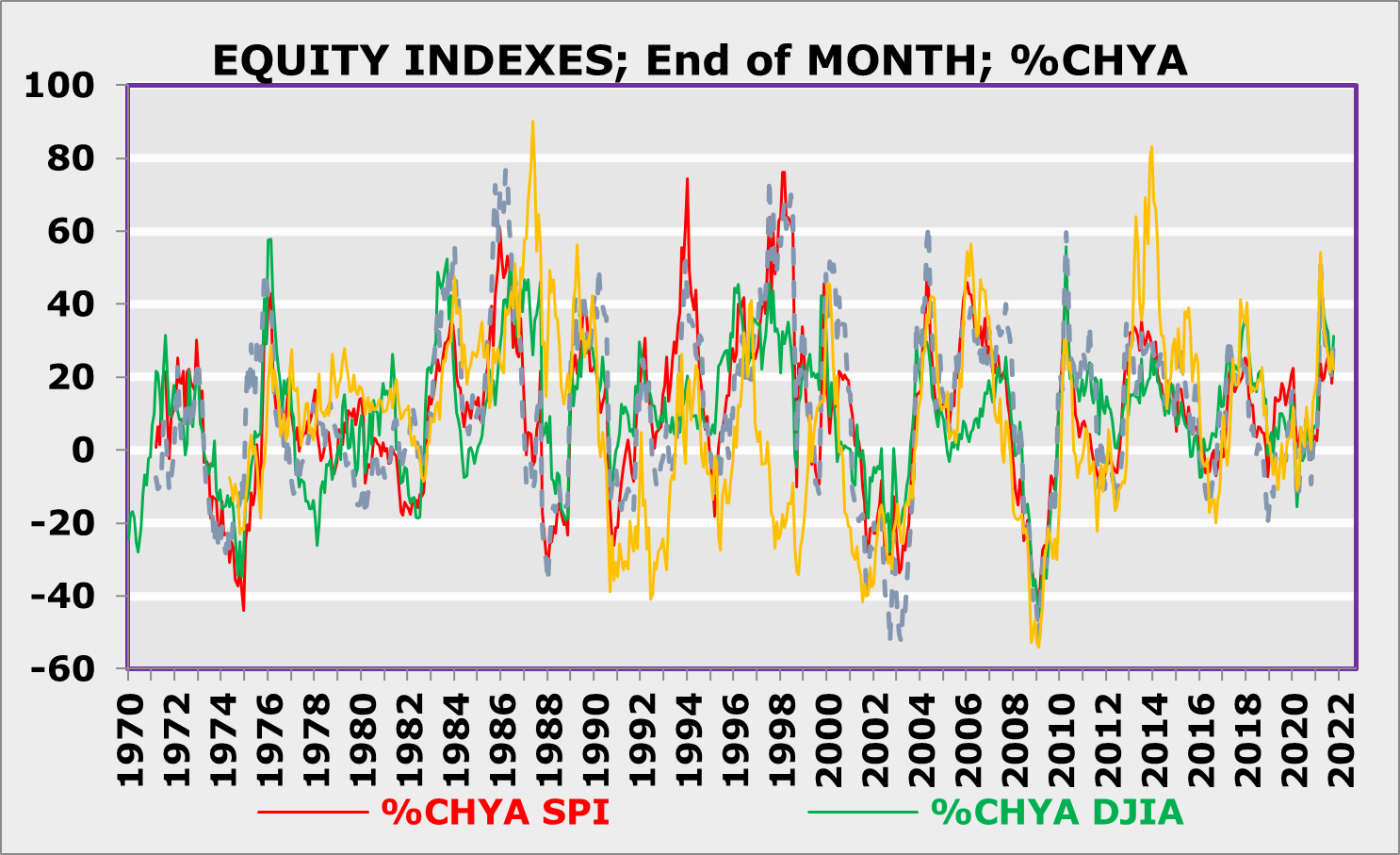

Before analyzing the developments of real GDP, we would like to show the development of the stock indices since 1970. The corresponding chart (below) shows substantial fluctuations in the annual averages. The chart is hardly exactly quantifiable, is it?

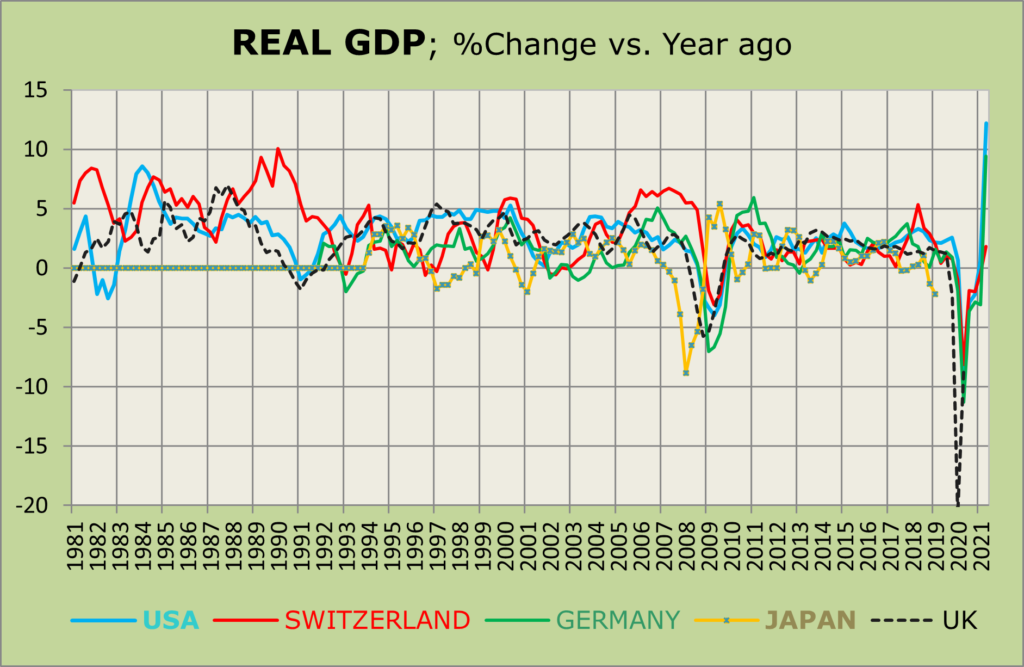

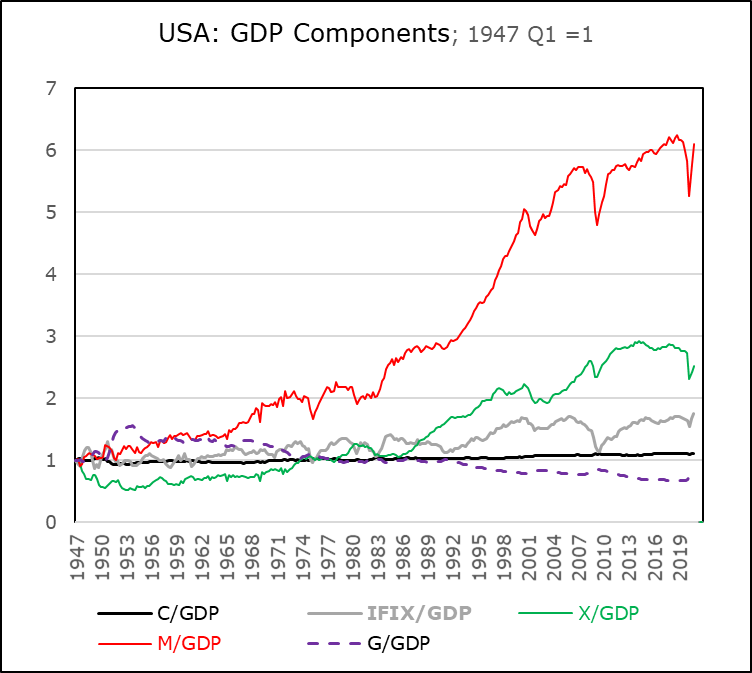

In our analysis of the economic performance, we focus primarily on the development of real GDP in Switzerland and the United States. At this point, we wonder what is the connection between the fluctuations of real GDP and the stock indices, as shown in the above graph.

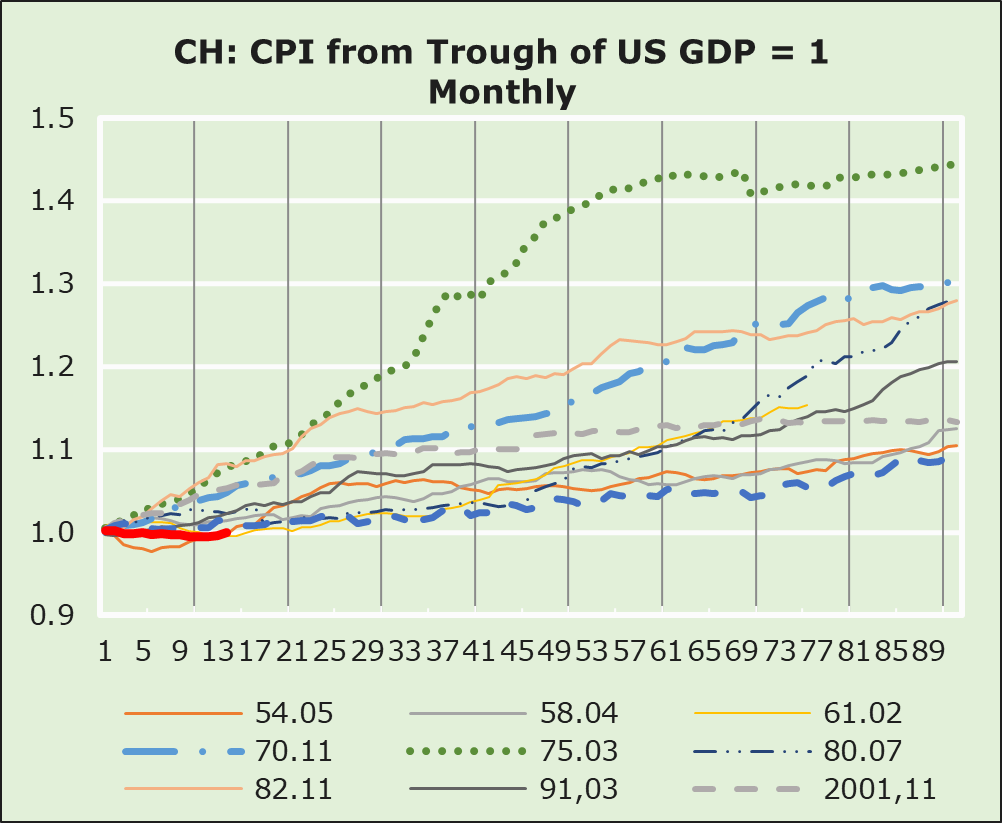

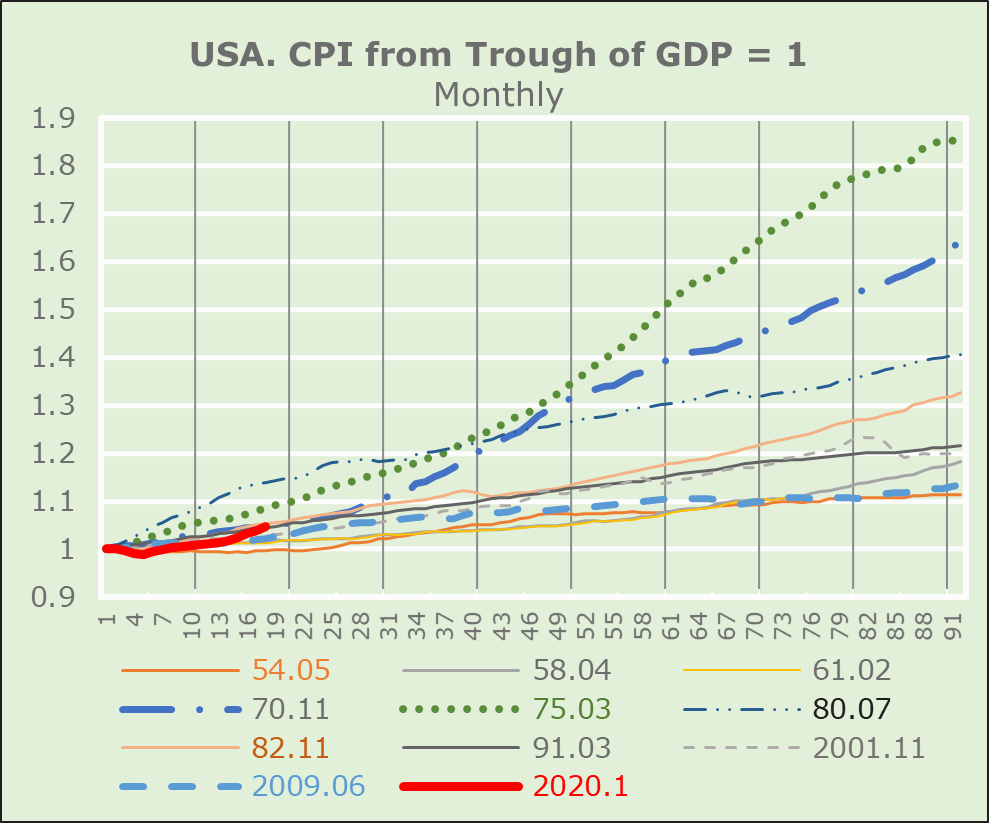

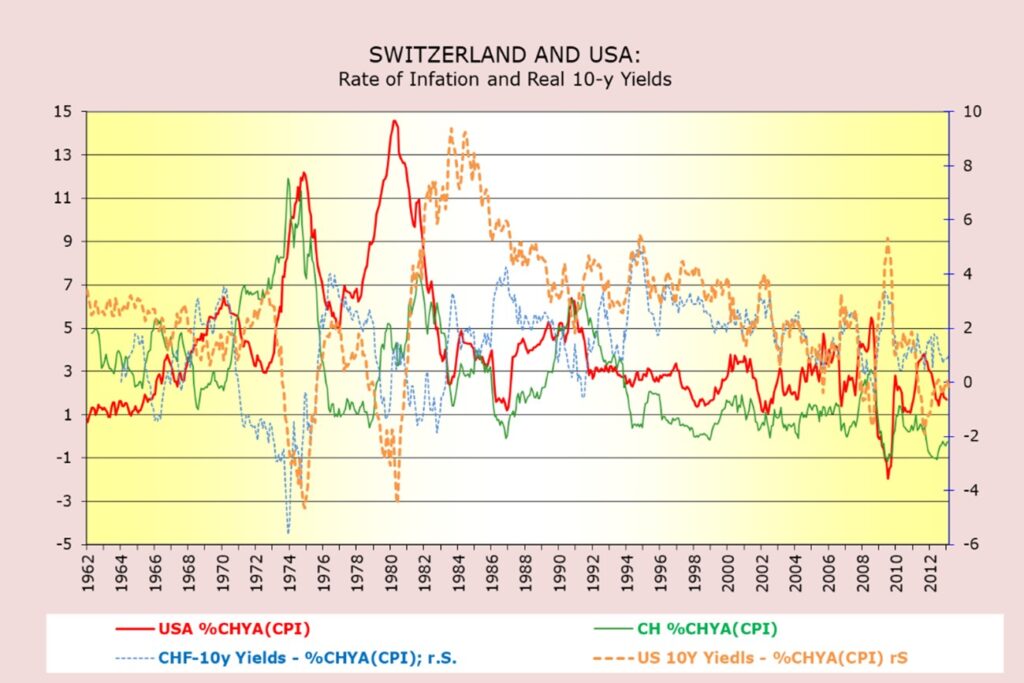

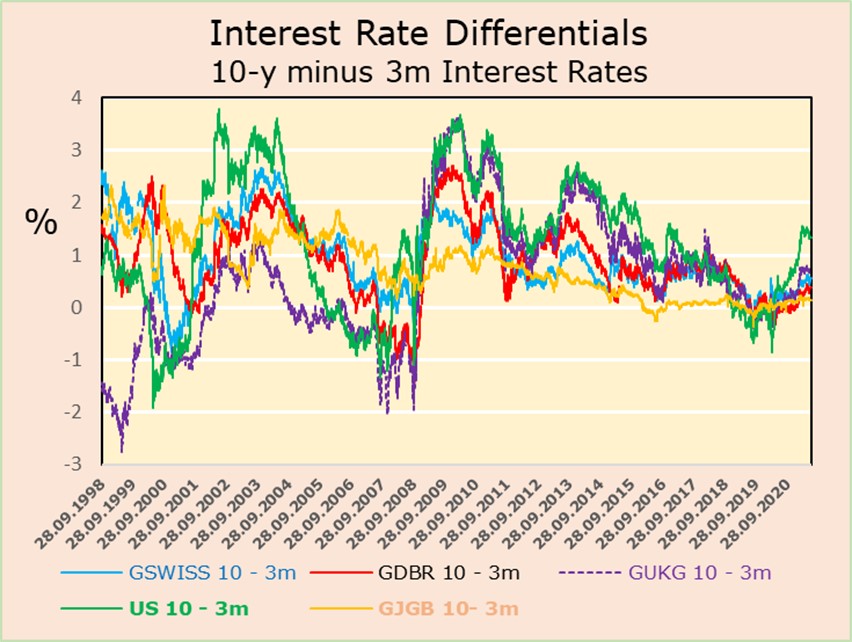

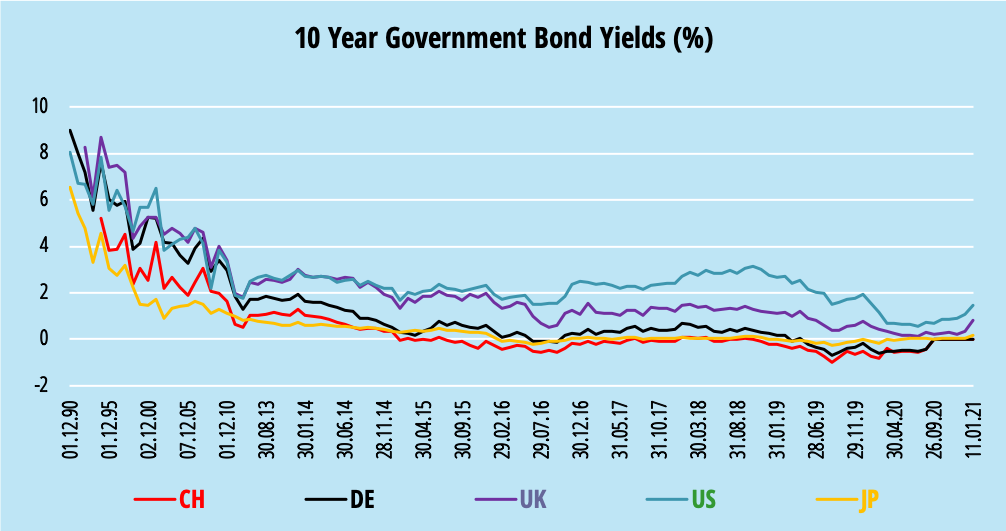

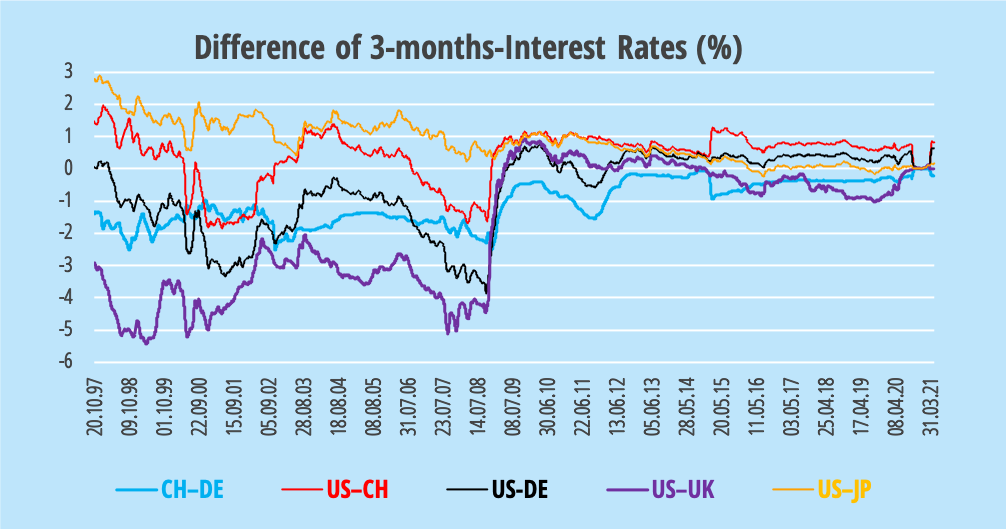

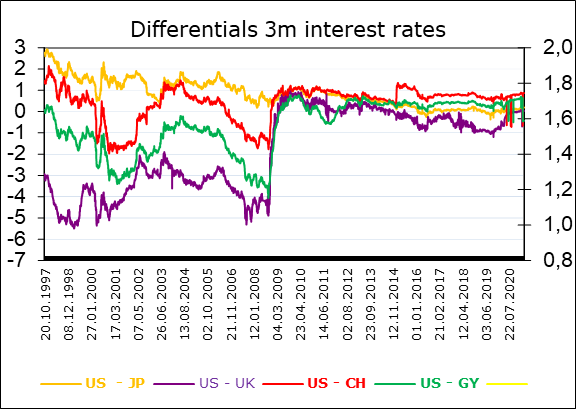

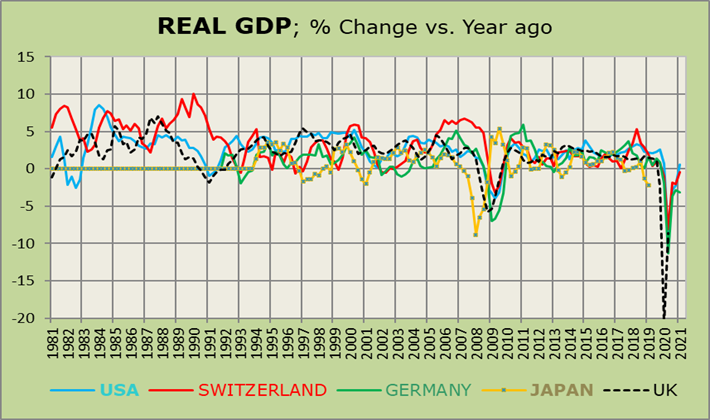

The available real GDP data for the five industrialized countries clearly show that there has never been an equivalent correction since the early 1980s, with the exception of the period from 2008 to early 2010! The chart shows that the Swiss economy reacted with a “substantial” lag to the downward corrections of real GDP in the U.S., Germany and the U.K. Developments in Japan are much more pronounced for the period 2002-2010.

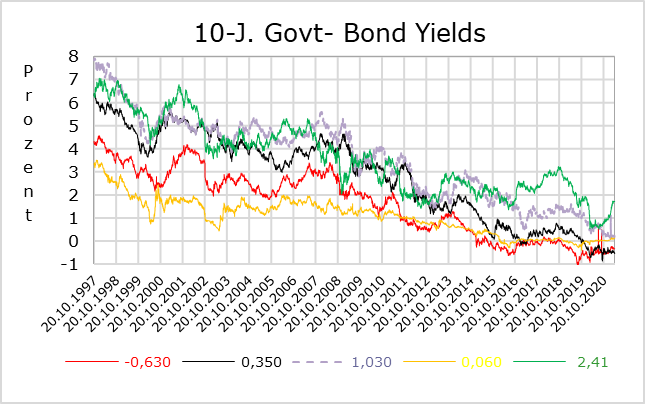

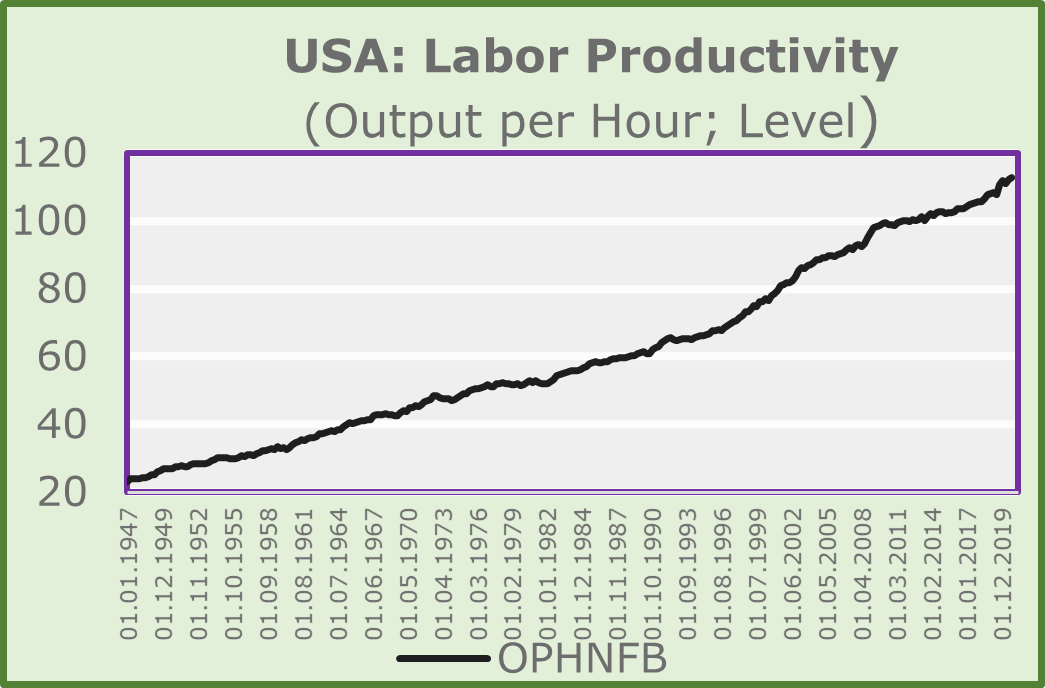

The diagram above indicates two very different developments. On the one hand, there was a fluctuating but steady increase from 1896 to the end of 1960, on the other hand, a dramatic, almost linear increase until 2021.

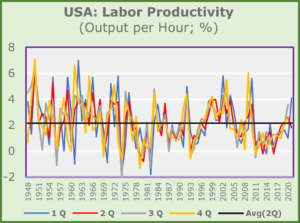

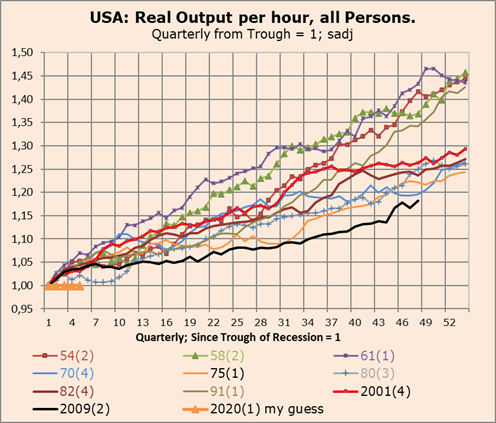

One of the main reasons for this can be derived from productivity developments. For the sake of simplicity, we again limit our analysis to productivity developments in the USA. We assume that they are also valid for Switzerland and other industrialized countries.

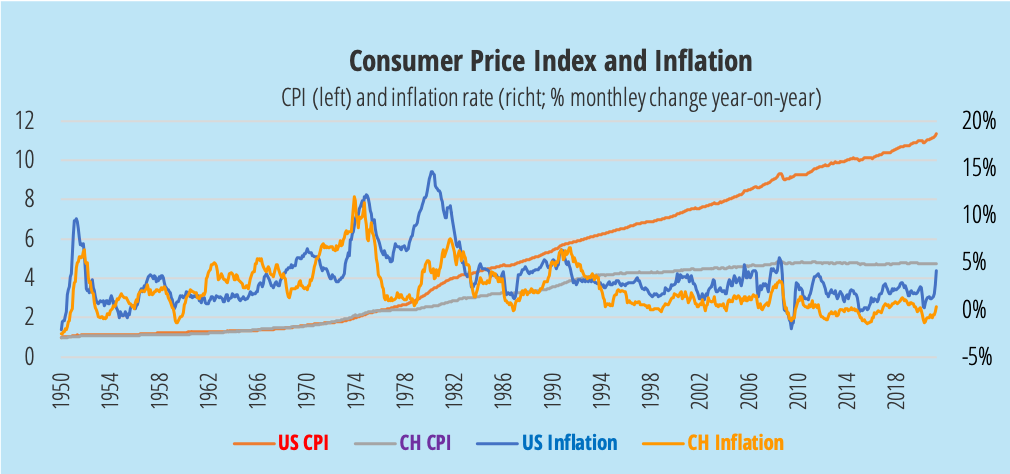

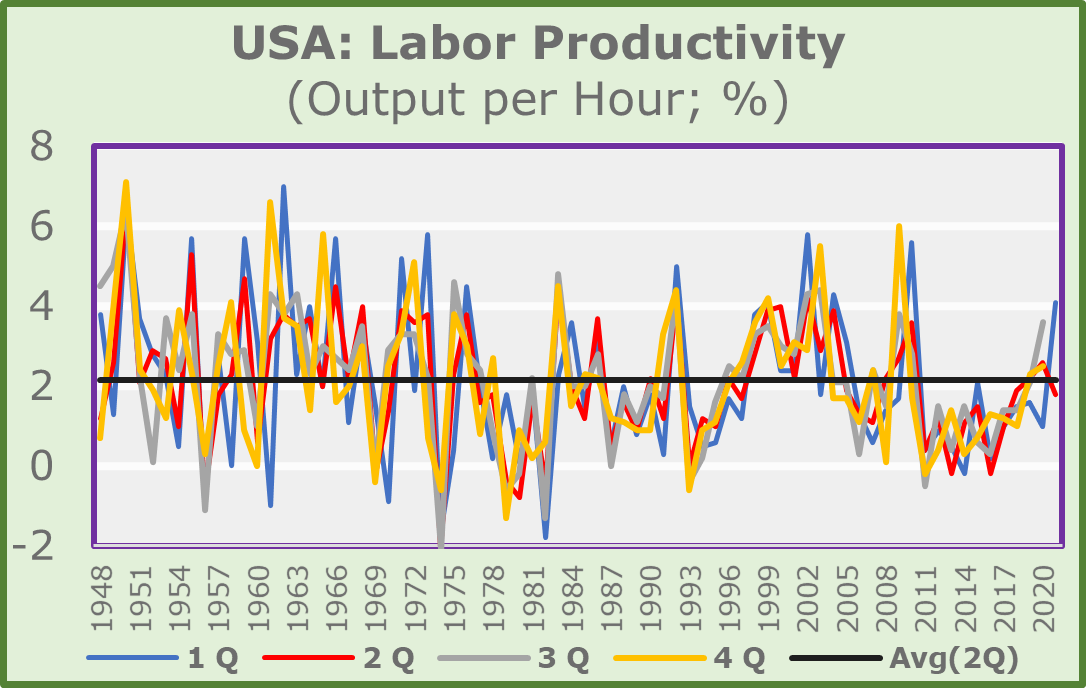

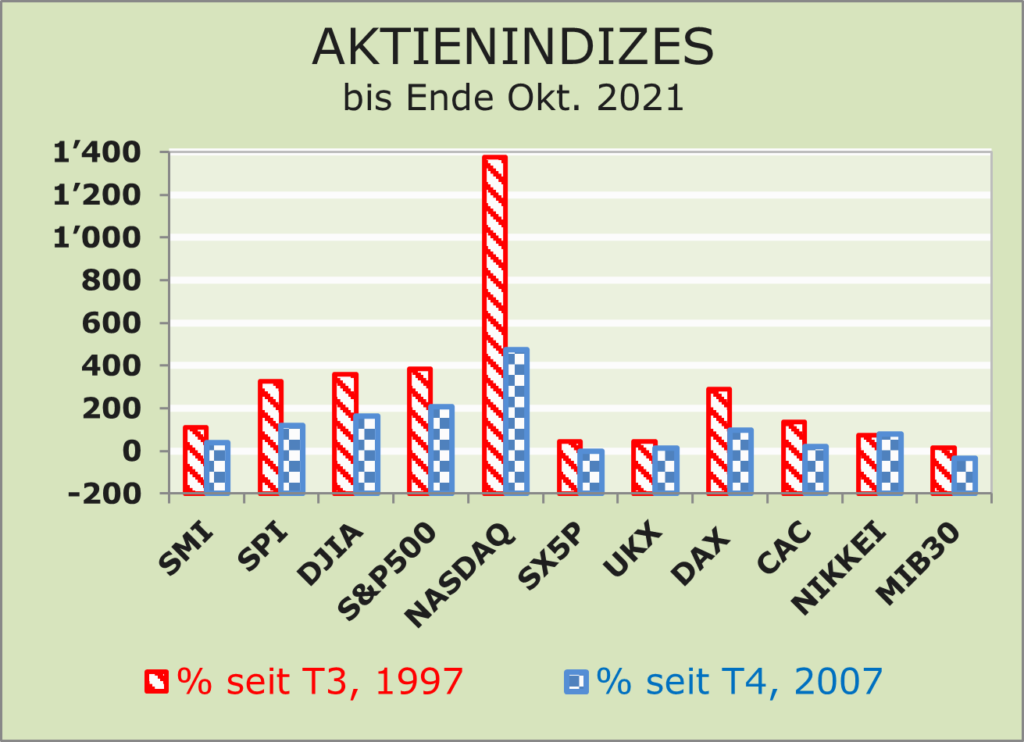

The level and quarterly rate of output per hour, as published by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, are much less volatile than real GDP, this measured by quarterly rates of change. Why this is so is the real question. Could it be that productivity is much more responsive to inflation – and especially to inflation expectations – than to economic activity? Long-term analysis, however, seems to suggest that productivity responds much more quickly to overall economic activity than to inflation! In recent years, productivity has adjusted strongly to sectoral changes. These developments were not so readily apparent at the macroeconomic level (real GDP). This is certainly due to the fact that companies have adjusted their production lines – and will continue to do so – much faster than reflected in macroeconomic data. New production lines require different inputs, both on a material and human basis. This has happened – and continues to happen – at both the firm and sectoral levels. In case you have a different opinion, let me draw your attention to recent developments on the stock price front. The differences between the various indices shown and the Nasdaq 100 Index speak volumes, don’t they?

We all know that certain sectors disappear over time while others emerge. Just think of the changes in the automotive industry in the past compared to the expectations of chip-controlled automotive production of today and especially tomorrow.

How to Benefit From Productivity Changes

Can you benefit from the expected/feared productivity changes? A somewhat difficult way to answer this very deterministic question implies that one should prefer stocks that have shown the best productivity performance in the past and have responded coherently to significant productivity changes, i.e. stocks of companies that recognize and quickly react to signs of a productivity turnaround?

If this approach does not satisfy everyone, there is another way, which is to reduce exposure to companies and industries with the worst productivity histories, either in the short term or, more importantly, in the long term. Our contextual argument is to take seriously the fact that turnarounds are sometimes quite dramatic, especially for companies or industries with high debt burdens. A dramatic productivity turnaround, such as the one we are currently experiencing, is often accompanied by dilutive financing and a high debt burden. In such a case, the substantive argument is “buy the problem solvers” or, to paraphrase a well-known slogan, “invest in the doctors, not the patients.”

Conclusions for Investors

Our conclusions should be seen as a specific consequence of an extraordinary shift toward technological innovation and away from the traditional “output per hour worked.” We should take the impact of new technologies ever more seriously.

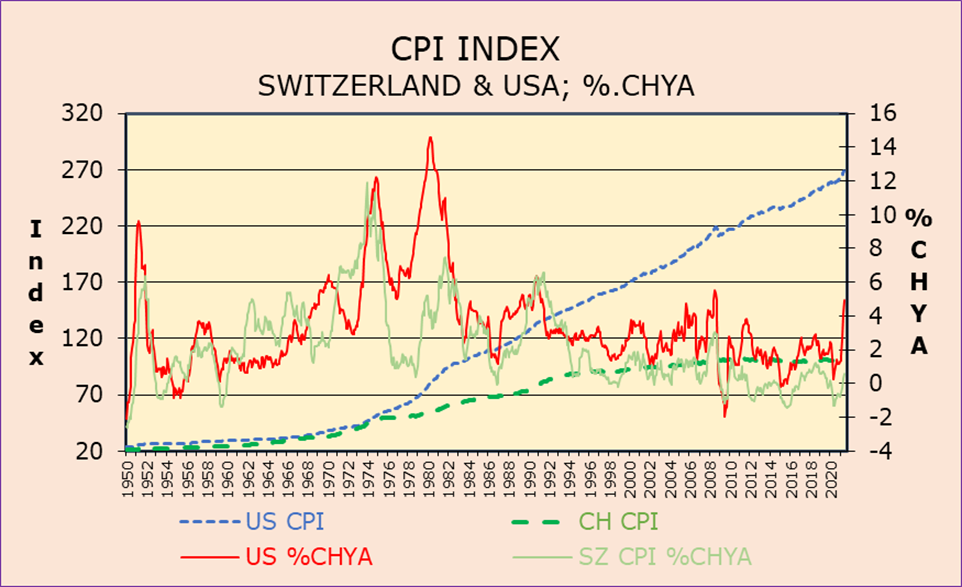

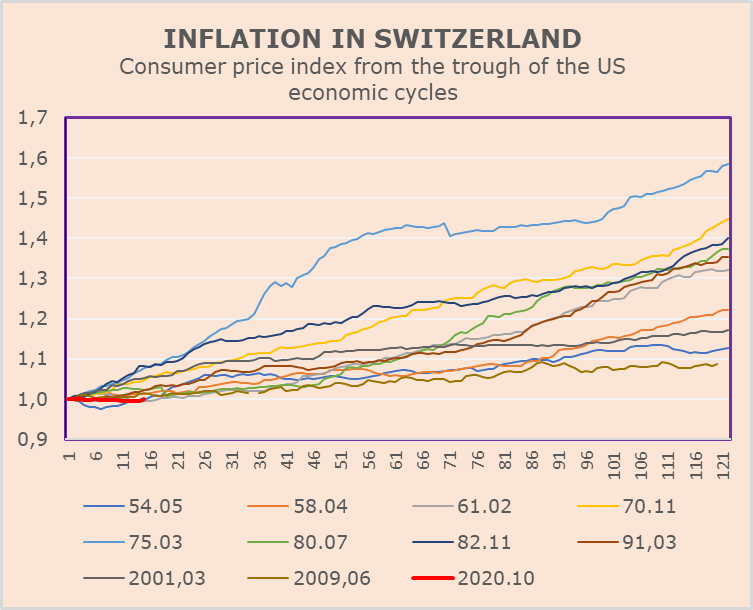

This also means that even if inflation fluctuates by 2% (which is considered historically low), equities would continue to perform better than fixed-income securities and money market instruments.

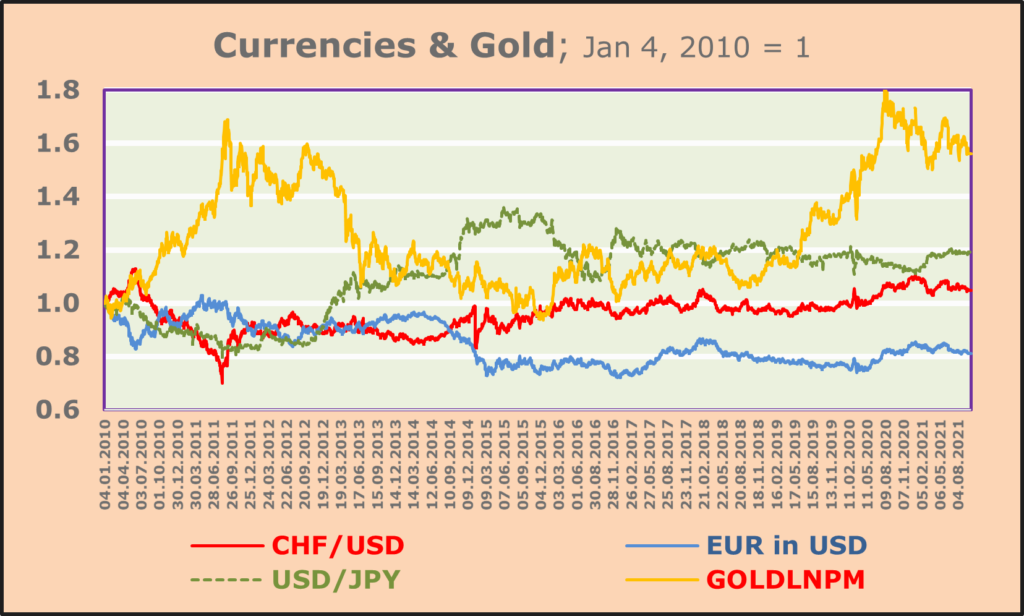

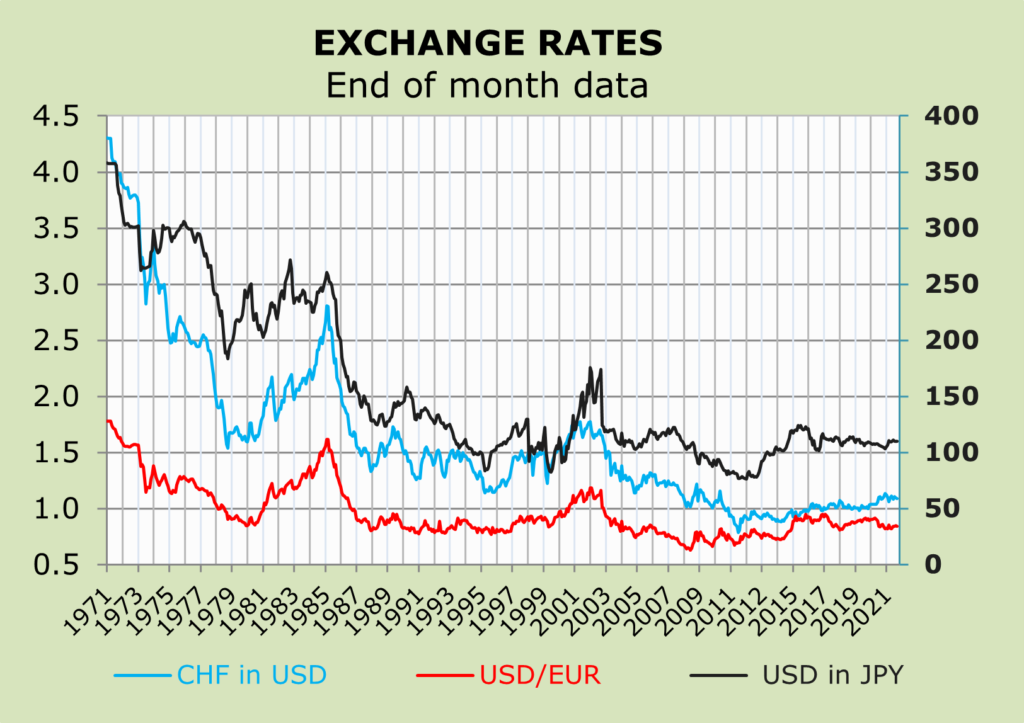

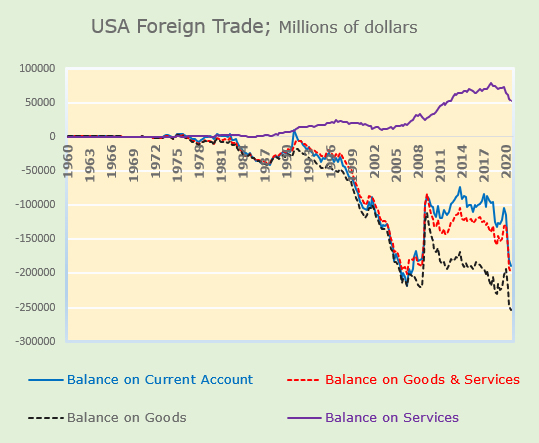

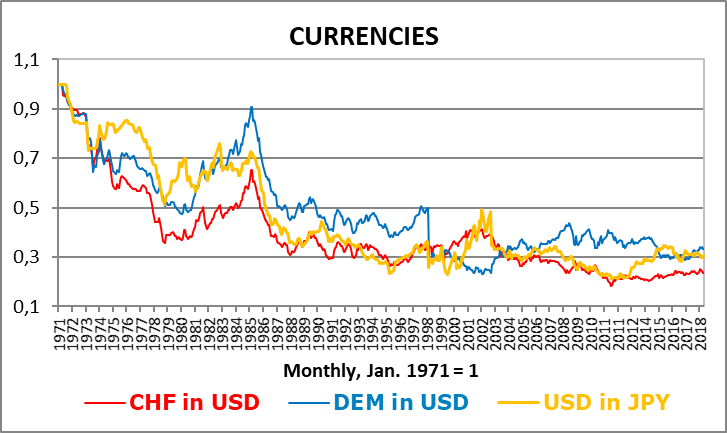

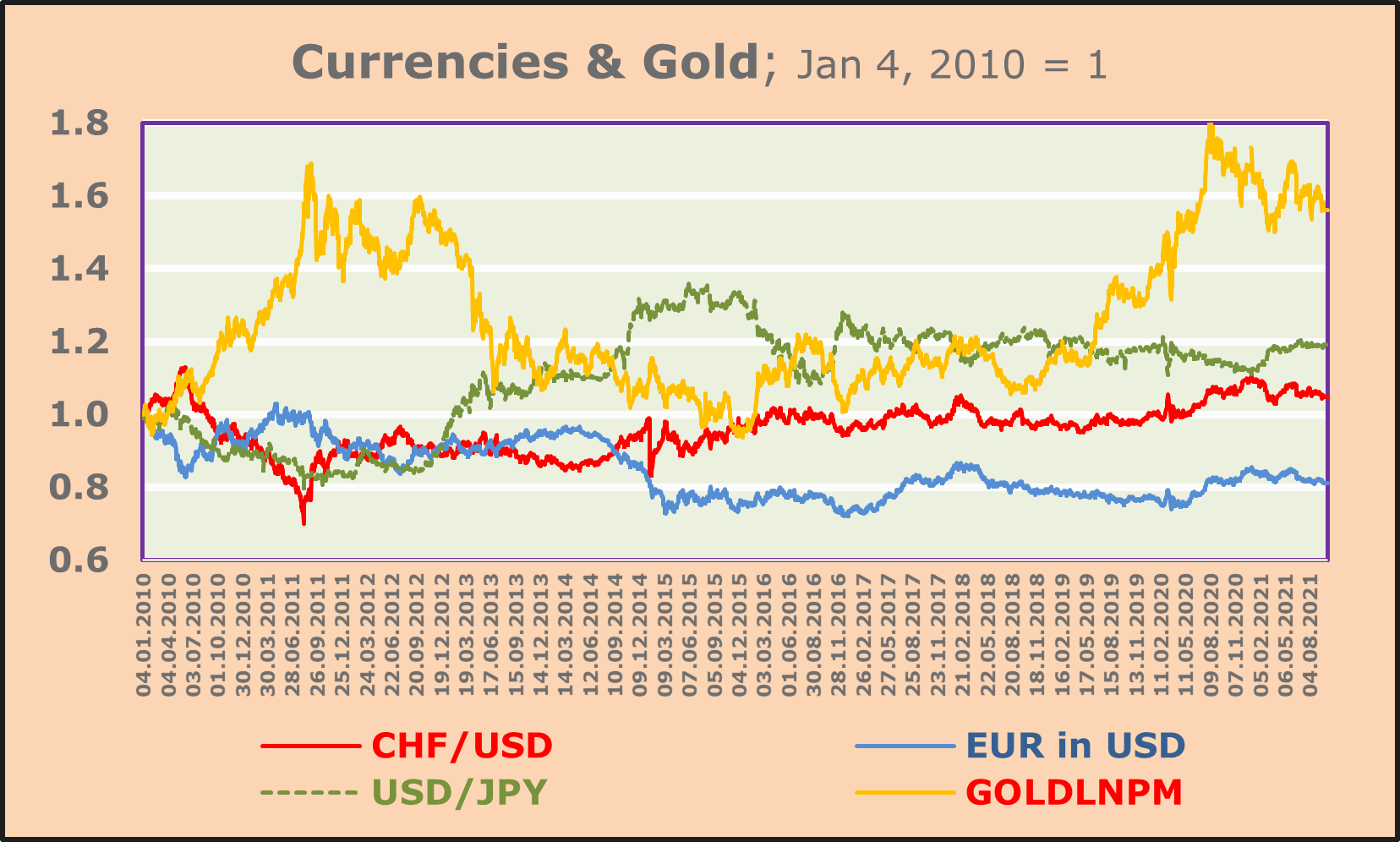

As a result, the USD is expected to rise against the EUR, the YEN and the GBP. The fact that the CHF, EUR and JPY have recently fluctuated in quite narrow ranges against the USD must be taken into account, also because the dark clouds in the currency sky do not bode well.

Any suggestion is highly welcome.